NICE methods and process evolution

Hear us discuss NICE's proportionate approach to technology appraisals on the NICE Talks podcast

In this podcast, hear from Victoria Jordan, Head of HTA and Market Access Policy at the ABPI, and Jen Prescott, Programme Director in process and operations for health technology appraisals at NICE. They discuss NICE's proportionate approach to technology appraisals.

ABPI response to NICE Proportionate Approach to Technology Appraisals

NICE has introduced the concept of taking a proportionate approach to technology appraisals (PATT) and has been working to test and implement changes to its process for health technology evaluation. In this paper, ABPI sets out its perspective on the PATT work programme, key principles it considers should be adhered to when developing new approaches to evaluating medicines, and next steps for further engagement.

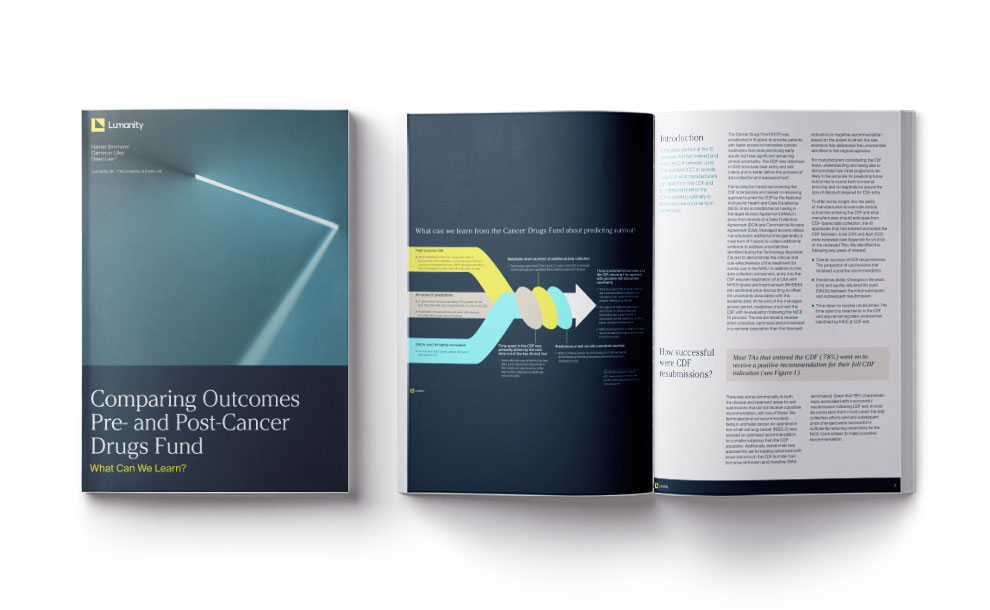

Comparing Outcomes

Pre-and Post-Cancer

Drugs Fund

Now that a number of medicines have exited the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF), the ABPI commissioned Lumanity to explore how it has been operating, including how well clinical outcomes are being predicted by manufacturers at the time of entry to the fund on initial appraisal. The findings are published in this report ‘Comparing Outcomes Pre- and Post-Cancer Drugs Fund: What Can We Learn?’

Could more medicines be recommended for routine commissioning rather than spending time in the Cancer Drugs Fund?

A new analysis commissioned by Victoria Jordan, Head of HTA and Market Access Policy at the ABPI suggests they could.

ABPI response to NICE review of how medicines and health technologies are evaluated

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a new Manual, which sets out how the latest medicines and health technologies will be evaluated. The ABPI made an assessment of the changes.

What is the new severity modifier being proposed by NICE?

How does NICE assess the value of a medicine?

In the concluding stages of the Methods and Process Review, NICE is now consulting on changes to methods and processes for conducting health technology evaluations.

The main thing NICE focuses on when making decisions is the ‘incremental cost effectiveness ratio’ or ICER, sometimes referred to as the cost per QALY (quality adjusted life year).

This estimates how much a medicine costs to provide one QALY, which is one additional year in perfect health.

NICE will usually decide a medicine is value for money for the NHS if it costs between £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY.

How does NICE make a decision and what is a modifier?

The main thing NICE focuses on when making a decision is the incremental cost effectiveness ratio or ICER. The ICER estimates how much a medicine costs to provide one QALY or quality adjusted life year, which is one additional year in perfect health.

NICE, will usually decide a medicine is value for money for the NHS, if it costs between £20,000 and £30,000 pounds per QALY. A modifier increases the value of the QALYs provided by the medicine.

It means NICE is prepared to pay more for medicine, if they judge it to be treating a severe disease.

By applying the QALY weighting, it decreases the ICER, making the medicine more cost effective.

The proposal to introduce a severity modifier was supported in NICE’s first consultation, reflecting views that the value of QALYs provided to patients with severe diseases, should be more than those with less severe diseases.

NICE’s committees also consider other factors that are important beyond the ICER, but the severity modifier will have the most influence on the committee's view of the cost effectiveness of the medicine.

What is a modifier?

Modifiers are factors that affect NICE’s decisions on health technologies. A modifier implemented in a quantitative way (as proposed for the new severity modifier) increases the value of the QALYs provided by the medicine.

It means NICE is prepared to pay more for a medicine if it treats, in this case, patients with a severe disease. By applying a QALY weighting, it decreases the ICER making the medicine more cost effective.

The proposal to introduce a severity modifier was supported in NICE’s first Methods Review consultation, reflecting views that the value of QALYs provided to patients with severe diseases should be more than those with less severe diseases.

NICE’s committees also consider other factors that are important beyond the ICER, but the severity modifier will have a direct impact on the committee’s view of the cost-effectiveness of a medicine.

How is NICE proposing to implement a severity modifier?

NICE will consider two measures of severity to decide whether the modifier is applicable: proportional shortfall and absolute shortfall.

What is proportional shortfall.

NICE is proposing to consider two severity measures to decide whether to apply a modifier.

One of them is proportional shortfall, which looks at the quality and quantity of life lost because of a disease, considering the existing treatment available to the patient.

Let's look at a simplified example, a person is expected to have 10 QALYs, but guess the disease which means they will only have 5 QALYs, the proportional shortfall is the number of QALYs they have lost because the disease, divided by the number of QALYs they were expected to have without the disease. In this case, that gives us a proportional shortfall score of 0.5.

If the disease means the patient will lose more QALYs, you can see that the proportional shortfall score gets higher and closer to one, the more life threatening the disease, the higher the proportional shortfall score will be.

If a medicine is treating a severe disease based on the score it is deemed to be higher value for the NHS.

Proportional shortfall

Proportional shortfall looks at the quality and quantity of life lost because of a disease, considering the existing treatment available to the patient, relative to the expected quality and quantity of life the patient should have without the disease. It gives a score between 0 and 1.

In a simplified example…

If a person is expected to have 10 QALYs but gets a disease which means they will only have 5 QALYs, the proportional shortfall is the number of QALYs they have lost because of the disease divided by the number of QALYs they were expected to have without the disease. In this case that gives us a proportional shortfall score of 0.5.

If the disease means the patient will lose more QALYs, the proportional shortfall score gets higher and closer to 1. The more life threatening the disease, the higher the proportional shortfall score will be.

Absolute shortfall

Absolute shortfall also measures the severity of the disease by considering QALYs lost, but it does so in an absolute way. It is a positive number that is not bound between 0 and 1. Going back to the simplified example, the absolute shortfall is just the number of QALYs the person with the disease loses, also considering the existing treatment available to the patient.

So, if they lose 5 QALYs the absolute shortfall is 5. If they lose more QALYs the absolute shortfall number increases.

The absolute shortfall will be high when the loss of QALYs over the patient’s life is large – so for example, conditions that are not immediately life threatening but have a significant impact on the health of a patient over time.

NICE is proposing that both the absolute and proportional shortfall scores for the medicine and disease are considered.

If the scores sit within NICE’s proposed ranges, a weight is applied that increases the QALYs gained by using the new medicine.

This is essentially placing more value on the health gains provided by medicines that treat severe diseases.

What is absolute shortfall?

The second measure NICE will consider when deciding whether to apply the severity modifier is absolute shortfall. This measures the severity of the disease by considering quality is lost, but it does so in an absolute way.

It gives a positive number that is not bound between naught and one.

If we look at a simple example, we can see the absolute shortfall is just the number of qualities, the person with the disease loses.

So, if they lose five QALYs, the absolute shortfall is five. If they lose more colleagues, the absolute shortfall number increases, the absolute shortfall will be high. When the loss of quality is over the patient's life is large.

So, for example, conditions that are not immediately life threatening, have a significant impact on the health of a patient over time. If a medicine is treating a severe disease based on this score, then it is deemed to be higher value for the NHS.

Why it is important NICE uses two measures of severity

Both absolute and proportional shortfall characterise the severity of a disease, however they both have limitations.

Absolute shortfall may be relatively small for older people with severe diseases, even those that are life threatening. And proportional shortfall may be relatively small for younger people with severe and debilitating diseases that are not immediately life threatening but experienced over many years.

Considering both measures enables NICE to capture and recognise a full picture of the severity of the condition in all types of patient.

Why ABPI supports this proposed change

The new severity modifier is a positive change that provides a broader definition of severity than the current end of life modifier. It will benefit patients with a wider range of severe diseases – NICE has stated for example, musculoskeletal, inflammatory and mental health conditions and childhood genetic diseases, in addition to cancer (which the current end of life modifier mostly focuses on).

NICE has proposed the severity modifier is implemented in a way that is “opportunity cost neutral”, prior to additional research being done to understand by how much society attributes more value to severe diseases.

We consider the guarantees on spending afforded by the Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access, and other cost containment policies already in place, should allow for greater ambition than this, and for the new modifier to benefit more medicines than is currently being proposed.

This would better align with the Prime Minister’s Life Sciences Vision and make a positive impact for patients with the most devastating diseases.

Video transcript

NICE has an incredibly important role in making sure that new medicines get to patients quickly and at a price that represents value for money.

But the methods that NICE uses needs to evolve to be fit for the future in evaluating the new medicines in the pharmaceutical industry pipeline.

ABPI fully supports the NICE Methods Review.

If we get this right, thousands of NHS patients will benefit from new cell and gene therapies and medicines for rarer diseases.

Industry is committed to a scheme to help the NHS manage what it spends on medicines.

This allows NICE to make the changes that are necessary, without risk to the NHS budget.

The case for change

For medicines, the review is linked to the commitments in the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access. Dr Paul Catchpole the ABPI's Director, Value and Access Policy explains the case for change.

Dr Catchpole and Victoria Barrett have written for PharmacoEconomics about the why the Methods Review is so important.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ensures we have a robust health technology assessment (HTA) approach in place for making decisions about which new medicines represent value-for-money and should be paid for on the NHS in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

NICE uses a standard measure called the quality adjusted life year (QALY) to work out how much health benefit a medicine provides regardless of what disease the medicine is used to treat.

The QALY contains two components: how much extra length of life taking a medicine gives a patient, combined with an estimate of the quality of that extra life.

However, it is well recognised that there are limitations to the QALY and how comprehensively it measures all the value of a medicine which is considered important by patients, their families and carers, the NHS and society.

In the evaluation of new medicines, NICE compares how much it costs to buy each extra QALY against an explicit threshold which represents the limit of how much the NHS is willing to pay.

This approach can be quite inflexible and makes it difficult for some types of medicines, especially those used in hospitals for treating specialist and rare diseases, to get approved for use on the NHS.

Video transcript

Pharmaceutical companies can’t pick whatever price they like, they have to think very carefully about how much value that medicine is offering patients, and society, and the NHS is a very strong customer in this country to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies.

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence looks very carefully at the clinical data around how well a medicine works, and looks at the price and works out if the price being charged by the company is worth it for the benefits that it brings patients and the health system.

NICE is widely respected around the world as one of the most rigorous institutions that scrutinises the value for money of medicines prices and so when NICE does approve a medicine in the NHS can have a lot of confidence that it represents very good value for money.

How medicines are priced

When setting the price of an individual medicine, companies will consider a number of factors including how well the medicine treats patients, how many patients might benefit from it, the value that health systems might place on a medicine in the disease area in question and the price of competing products.

The new medicines that the pharmaceutical industry is researching in clinical trials have dramatically changed over the last ten years from being predominantly treatments for long term chronic conditions and late stage cancers to being more targeted therapies for complex, sub-diseases with increasingly smaller patient populations.

Advances in research and development mean we are now seeing more therapies for treating patients earlier on in their disease and which in some cases can potentially cure the patient. These medicines often address a very high unmet medical need because there are either no, or very few, other treatment options available for the patient.

Many of these types of new medicines are having difficulty navigating NICE’s current methods of evaluation and so the Methods Review that NICE is undertaking is a real opportunity to change this.